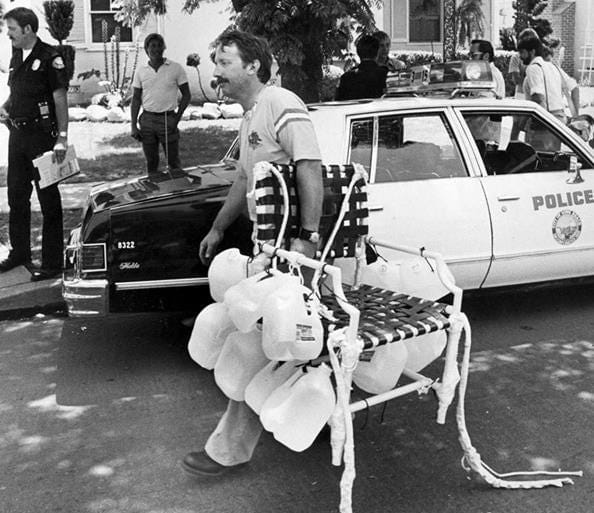

In 1982, multiple commercial pilots reported sightings of “a man in a lawn chair with a rifle” floating over LAX airport.

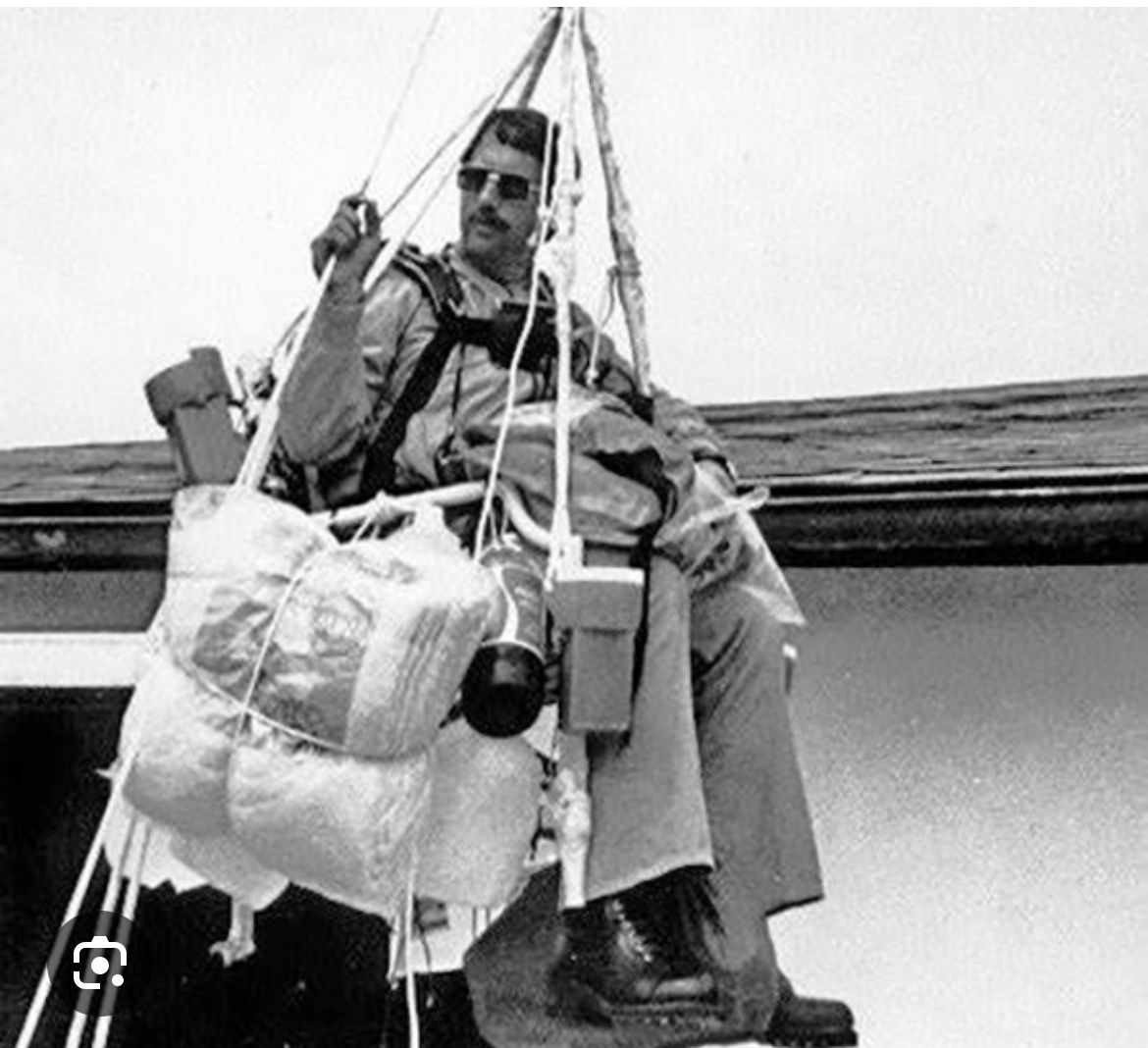

See, Larry Walters, a 33-year-old truck driver, attached 45 helium-filled weather balloons to a Sears lawn chair. He armed himself with some sandwiches, a few beers, a CB radio, and a pellet gun.

He expected to float gently a few hundred feet above the ground for a scenic beer cruise over the neighborhood. (I think we both know, that’s not what happened.)

As soon as his friends cut the tether, Larry shot up to 16,000 feet—that’s nearly three miles high, smack in the middle of LAX airspace.

Larry spent 45 minutes freezing at altitude before using the pellet gun to pop a few balloons, which—shockingly— worked. He descended slowly, drifted into some power lines (causing a blackout in Long Beach), and was promptly arrested. He had traveled 21 miles.

See, Larry always wanted to be a pilot, but his poor eyesight kept him from his lifelong dream. Instead, Walters took matters into his own hands and almost froze to death at 16,000 feet in a $13 Sears lawn chair.

Clearly it wasn’t just his poor eyesight that kept him from the cockpit. See, Larry failed to contemplate the most basic concepts of air flight. Things like wind direction, which blew him into LAX airspace. Or, the most basic application of lift and drag, which almost cost him his life.

Crazy Larry didn’t just defy air traffic control—he became a textbook example of what psychologists would later call the Dunning-Kruger Effect. It’s what happens when you’re too incompetent to realize your own incompetence. Larry didn’t need flight school—he needed a mirror.

Dunning Kruger

In 1999, researchers David Dunning and Justin Kruger set out to determine whether people with low ability tend to overestimate their competence.

Did you know that I have 135 articles recorded and ready for your listening pleasure on Spotify? This link will take you directly to my podcast home page on Spotify.

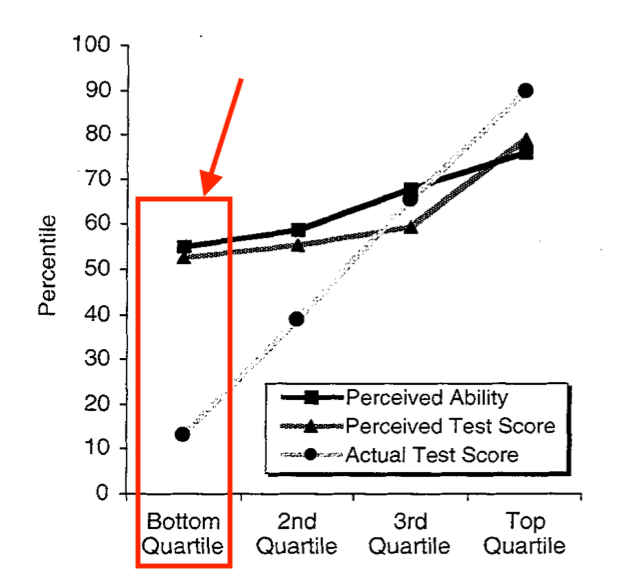

Not surprisingly, Dunning & Kruger confirmed what we all know. That people with the least competence are often the most confident. Or as President Kennedy’s speech writer Theodore Sorenson once wrote, “often wrong, seldom in doubt.” Blink twice if you know someone like crazy Larry.

As the graphic below illustrates, people with the highest perceived ability and test scores {orange rectangle} tend to perform in the bottom quartile.

Courtesy of Unskilled and Unaware

So, why are some people like this? Why can’t they realize their own incompetence before they open their mouths? Or, place a $1,000 bet in an NBA game. Or strap themselves to a Sears lawn chair.

“By the grace of God I fulfilled my dream,” he told the gathered crowd. “But I wouldn’t do it again for anything.”

It’s low competence and high confidence that often gives “main character energy". It’s slang for someone who prioritizes themselves and often shows extreme overconfidence and self assurance.

Unknown Unknowns

Because, the same skills that help you perform well at something are often the same skills you need to judge your own performance. So if you’re bad at something, you’re also probably bad at realizing how bad you are. It’s why the first guy on the dance floor at a wedding is usually the worst dancer. It’s a triple whammy of ignorance: not knowing, and not knowing that you don’t know.

The Blame Game

When we fail or underperform, our brains do some emotional jujitsu to make us feel better about ourselves. This usually results in blaming another person for our own incompetence. Like failing a high school algebra test and blaming the teacher. This kind of blame game helps buffer our ego from shame, embarrassment, or existential dread.

It’s the reason why sports betting is ruining sports.

The Expert’s Gambit

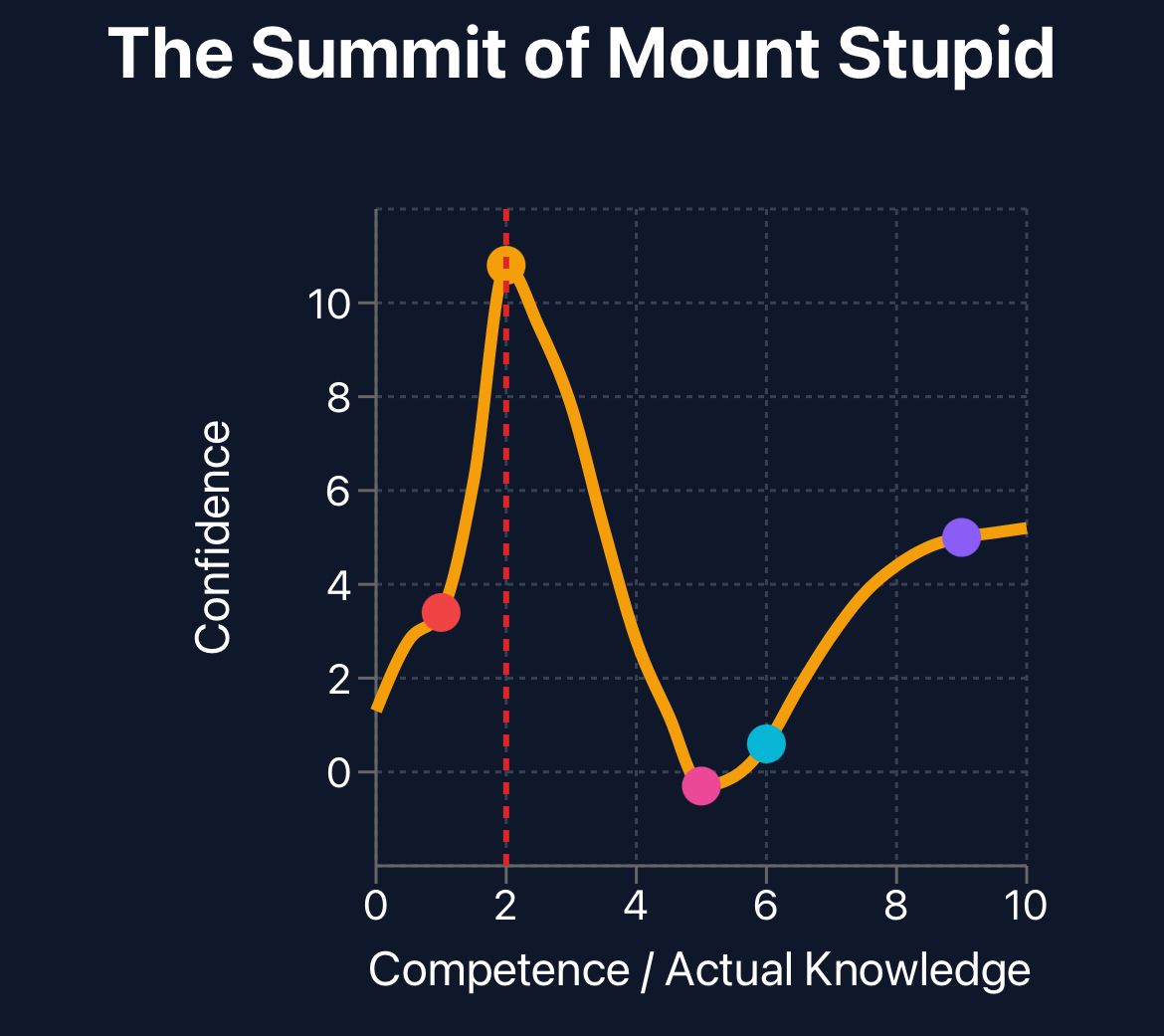

Ironically, people with true expertise often underestimate their competence. They assume, “If I find this easy, surely others do too.” Their curse is knowledge—they forget what it was like to not know

People who are brand new to a subject often experience a burst of confidence. Like playing Chess for the first time. It seems straight forward enough until you watch The Queens Gambit. It takes that kind of wake up call to realize you don’t know a skewer from a mating net.

This faux expertise is sorta the “summit of Mount Stupid” on the “Dunning-Kruger curve.” They’ve learned just enough to feel empowered, but not enough to realize the vast ocean of things they don’t know.

Confidence Culture

We live in a society that rewards confidence more than competence. The loudest talking head on TV often wins the argument. People with little expertise label themselves as “thought leaders”.

The Dunning-Kruger effect isn’t just a quirky psychological glitch—it’s a cultural epidemic. Because this phenomenon isn’t limited to ballroom dancing and chess.

The epidemic is much more problematic when your overconfident Doctor chooses not to run certain tests. Or, your accountant chooses to ignore certain tax rules and regulations. Or, your incompetent financial planner chooses to ignore economic red flags and puts your hard-earned money at-risk.

The Big Finish

The Dunning-Kruger effect also fuels terabytes of know-it-all posts on Social Media. It leads to a great deal of political polarization over subjects most of us don’t fully comprehend. And, it leads to some historically horrific decision-making.

The antidote? A little humility, a lot of learning, and the wisdom to know when to sit down and let someone else fly the lawn chair.

Have you ever come across a nutter like crazy Larry? A guy with no competence but an enormous dose of confidence? I want to hear about it. Leave a comment below. I promise to read it and respond to you. Hey, maybe we’ll end up being friends.

Hey, real quick, if you learned something from this article or it makes you think of your crazy Uncle Buck who’s a legendary know-it-all, would you mind forwarding it to someone you care about? I bet they’ll get a good laugh.