Have you ever wondered how those people in TV ads lose so much weight by taking a pill, while you gain five pounds just driving past a Dunkin’ Donuts?

The answer is simpler than you might think. Sure, they could be lying, but the before-and-after pictures suggest otherwise—they’re impressive. The simple truth is that these “clinical” studies are conducted across very, very large groups of people. Here’s how it works.

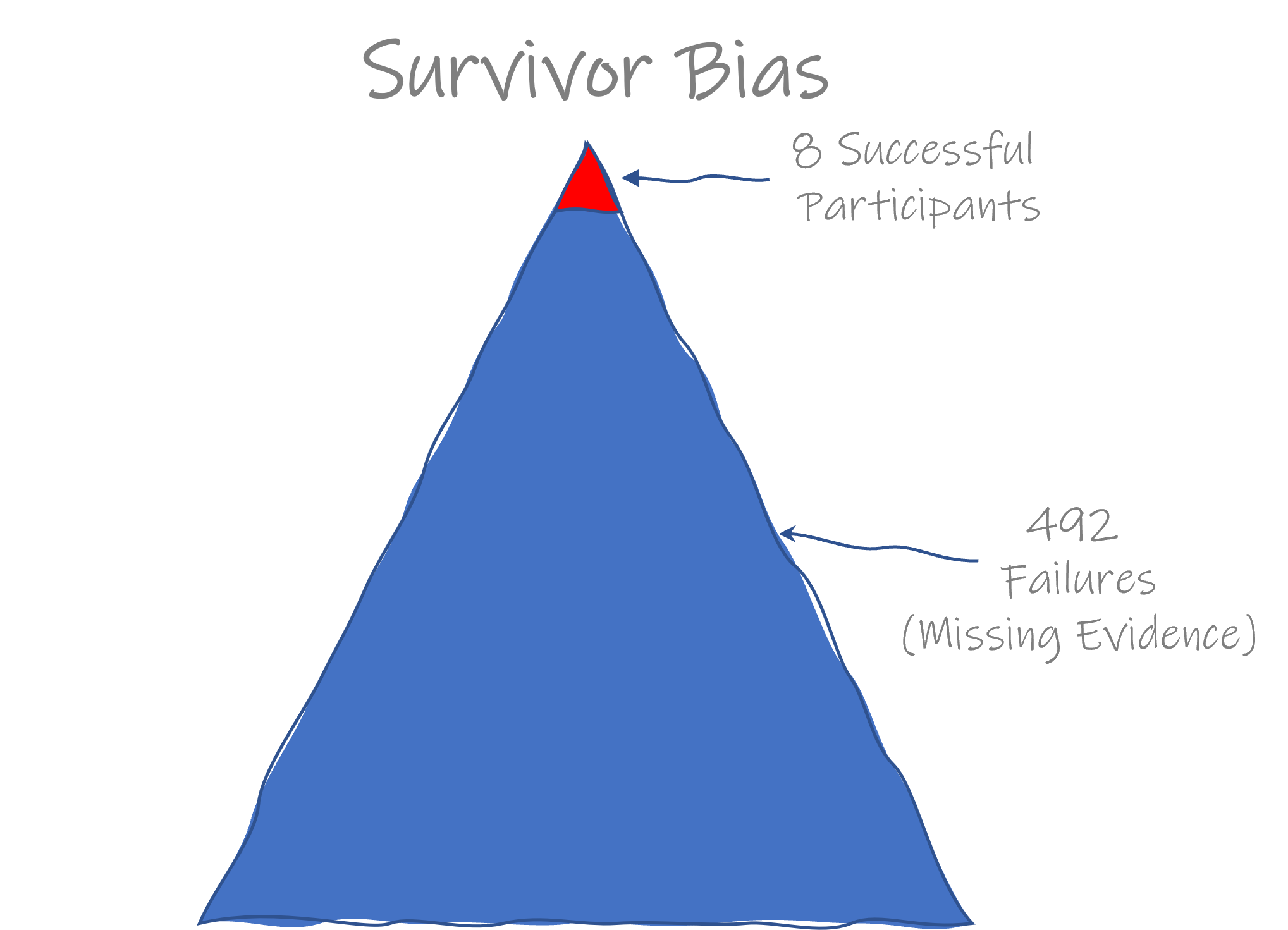

First, find 500 volunteers who want to lose at least 25 pounds. That should be easy. Each volunteer agrees to participate in exchange for free diet pills.

Second, organize monthly weigh-ins and dismiss the bottom 20% of participants each month. By the end of the sixth month, you are down to 8 participants. Guess what? Those 8 participants will have lost significant amounts of weight.

However, all you see in those television ads are the eight people who now look like middle-aged supermodels. How on earth did they do it?

The message you are meant to believe is that everyone on the magic pill loses 20 pounds and suddenly has rock-hard abs. (Blink twice if you’ve ever fallen for this trick.)

What you don’t see are the 492 participants who lost little weight—or none at all. They are the missing evidence that proves those magic weight-loss pills don’t really work. Make sense?

The Survivor Bias

This type of marketing plays on a cognitive theory called Survivor Bias. It’s a form of selection bias that occurs when an evaluation considers only existing or “surviving” observations while ignoring those no longer present.

We ground ourselves in the seen and systematically ignore the unseen.

Take Felix Baumgartner, the 43-year-old Austrian daredevil. About ten years ago, he took a helium-filled balloon to 128,000 feet above the earth. Then, he jumped. Baumgartner executed a supersonic freefall lasting three minutes and forty-eight seconds, reaching speeds up to 843.6 mph. Click the image below to watch this nutjob jump. (Spoiler: he survives—barely.)

His sponsor, Red Bull energy drink, employed survivor bias. They were trying to communicate that adventure is exciting—and safe.

Yet, Red Bull never mentioned the hundreds of people who had tried similar feats and failed. Why? Because all those people are dead. They represent the missing evidence that jumping out of a perfectly good airplane—at any altitude—is a terrible idea.

Courtesy: Kamil Pietrzak

According to the United States Parachuting Association, 10 individuals died from parachuting accidents in 2023.

High School Blues

Survivor bias is also the reason every angsty high school boy goes through a period where he doesn’t want to go to college. Why? Because, you know, Mark Zuckerberg, Steve Jobs, and Bill Gates didn’t go to college—or simply dropped out.

Image courtesy of Djim Loic via Unsplash

All three ended up being zillionaires. If Bill Gates spent $1 million per day, it would take him 400 years to spend all his money. (Okay, that little factoid has little to do with survivor bias, but I couldn’t help myself.)

The zillionaire sample set is totally flawed. What the high school kid doesn’t see are the millions of dropouts struggling to pay their bills. They are the missing evidence that college is still the best way to become financially independent.

What’s likely missing in your life is my buttery smooth voice in your AirPods. You can follow Wit & Wisdom on Spotify, Apple iTunes, iHeart, or wherever you get your podcasts. See what I did there?

The Flying Fortress

Perhaps the best example of survivor bias comes from World War II. During the war, American air forces relied heavily on the B-17 Flying Fortress bomber.

These workhorses dropped more bombs during World War II than any other aircraft and are featured in the incredible Apple TV+ show Masters of the Air. (Click below to watch the trailer. It’s amazing.)

Black Thursday

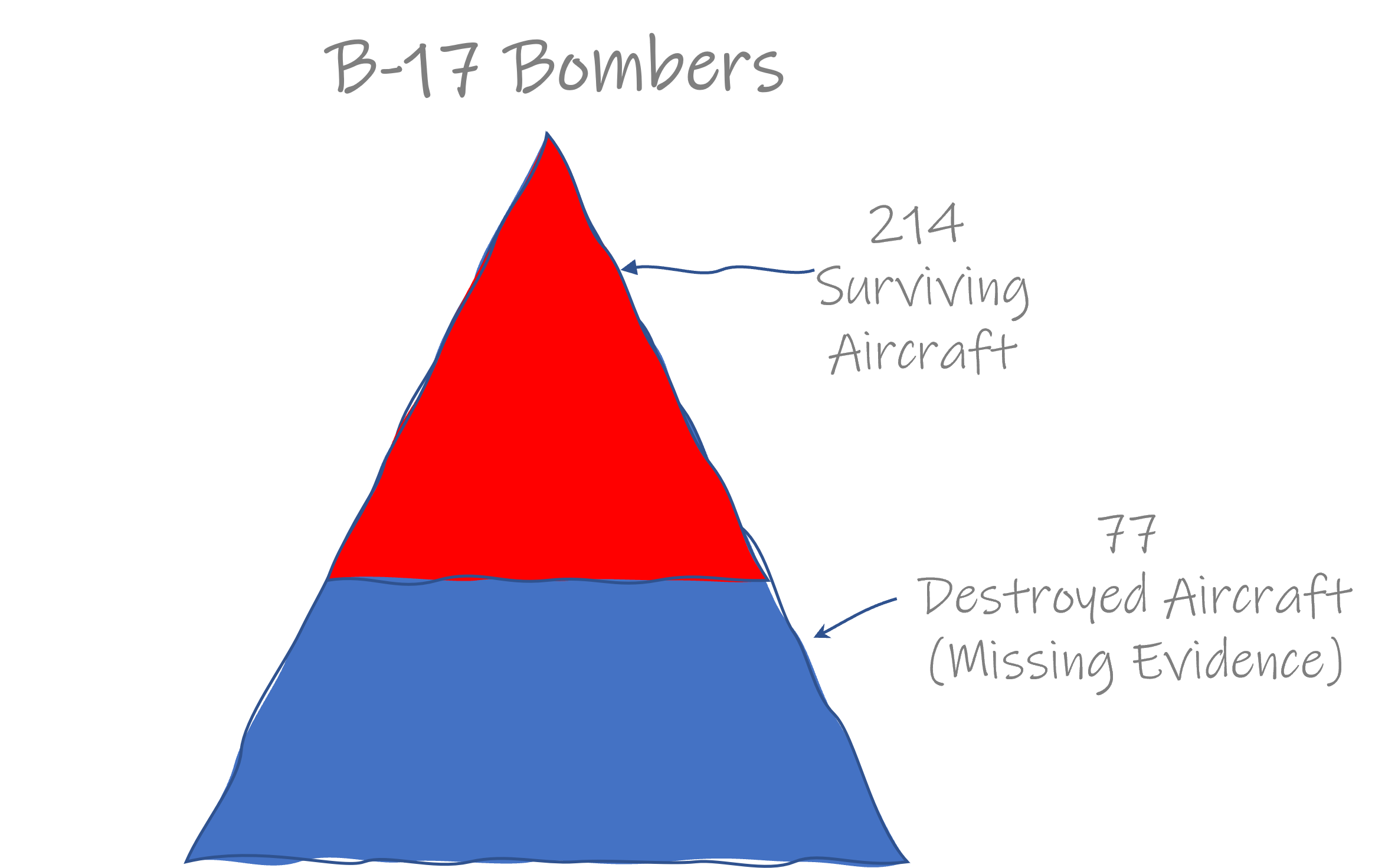

On October 14, 1943, a large fleet of four-engine heavy bombers launched an air raid on German ball-bearing factories. The attack, later infamously dubbed Black Thursday, resulted in staggering losses of both human life and 77 B-17 aircraft.

Enhancing the Fortress

American military leaders wanted to determine how to reinforce the planes to make them more defensible against German fire? Simply reinforcing the B-17’s undercarriage would add too much weight, reducing the aircraft’s range and payload capacity.

The 77 downed aircraft that crashed and burned over Schweinfurt, Nazi Germany, taking their invaluable data to a fiery grave. Experts needed to know why those 77 aircraft failed to return to base. They represent the missing evidence that would have proven where the planes were most vulnerable.

Still, what if the 214 surviving aircraft could provide the necessary data to effectively reinforce the airplane?

By examining the damage to the 214 surviving aircraft, military leaders could ascertain where to reinforce the planes, making them less likely to crash in battle.

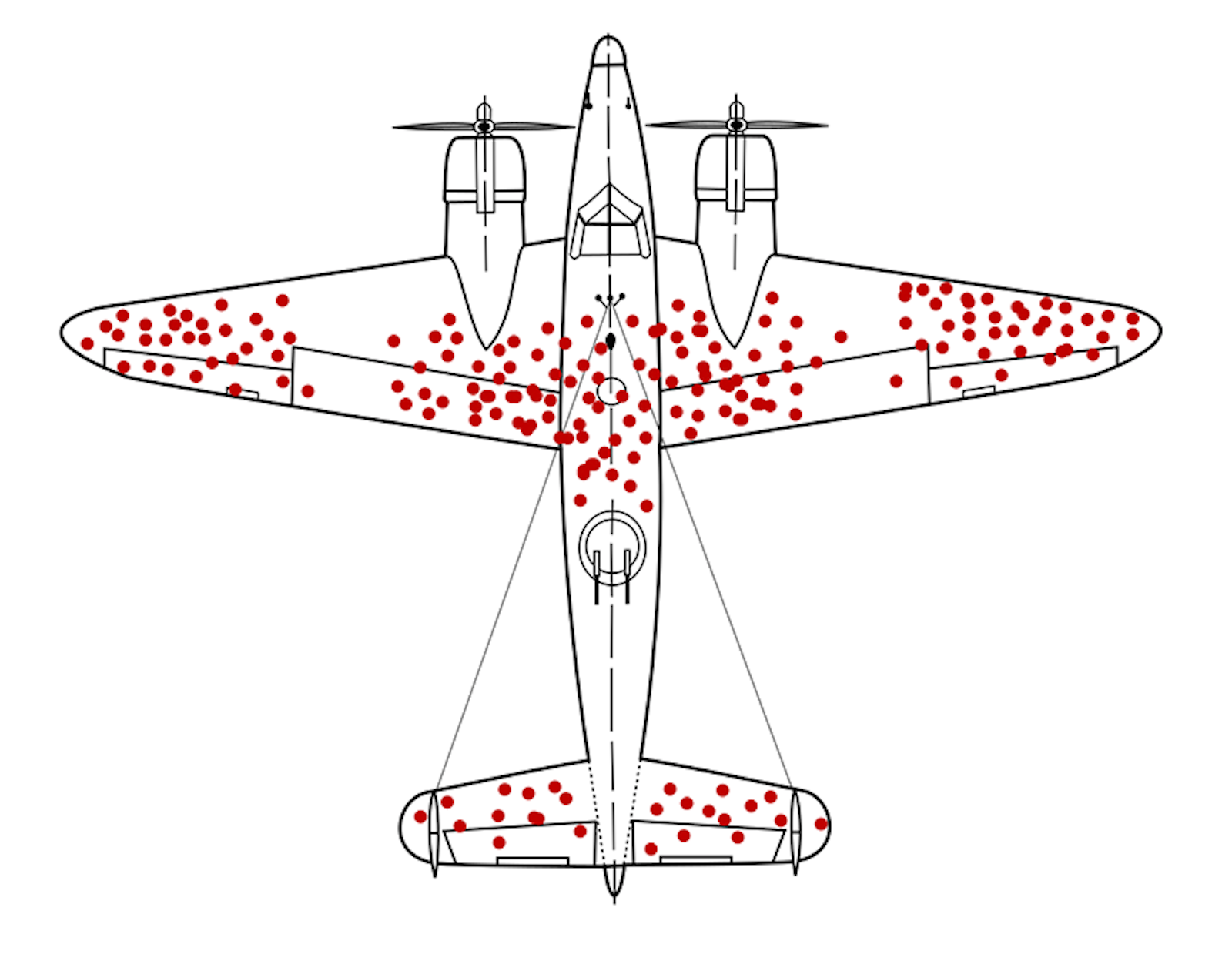

Image by Martin Grandjean / Wikimedia Commons. Areas most commonly hit in returning aircraft.

Unfortunately, examining the most frequently hit areas of the surviving aircraft would lead to flawed conclusions. As a result, the damage is only indicative of shots that missed their mark, and the planes continued flying. The most heavily damaged planes never made it home.

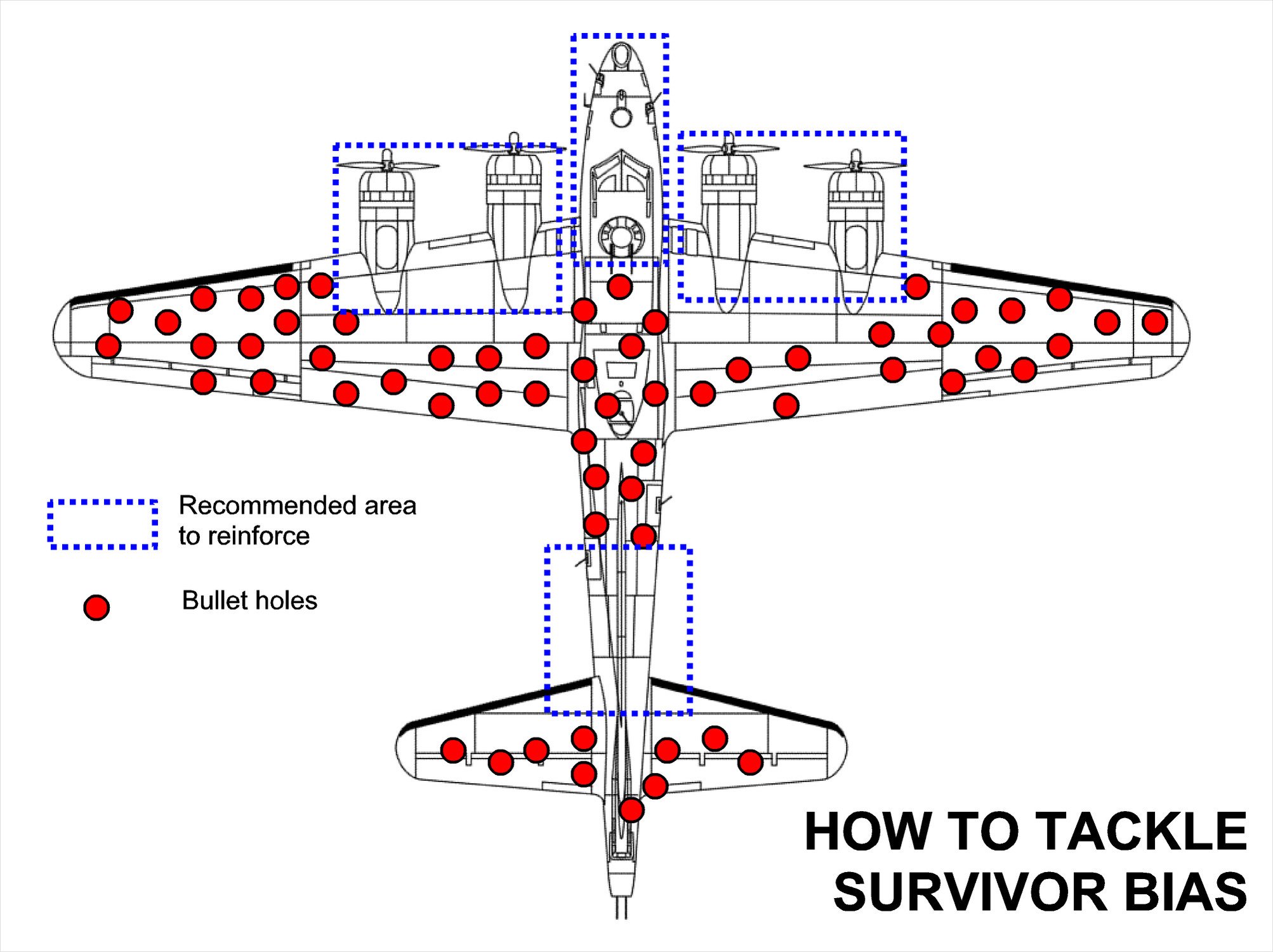

With the help of Abraham Wald, a mathematician and famous statistician at Columbia, the team of military experts realized their error. By reviewing the surviving aircraft, military experts could surmise which parts of the surviving aircraft had not been hit. (See sections in blue, below.)

Image courtesy of José Pablo Luna Sánchez

That was the missing evidence. They began fortifying the remaining B-17s in the areas deemed most vulnerable to German anti-aircraft fire.

Alrighty, we’ve learned a lot here today about weight-loss scams, diet pills, billionaire high school dropouts, and WWII bombers. The real magic, though, is understanding Survivor Bias.

See, it’s almost always the missing evidence that nobody wants us to see—evidence that debunks the unbelievable. Evidence that immediately explains the unexplainable.

So, the next time you’re asking yourself, “How could that be possible?” remember to look for the missing evidence.

Have you ever made a really bad decision because you didn’t see the missing evidence? I’d love to hear from you. I write purely for the joy of making new friends, so please reach out and tell me what’s on your mind.

Click the button below to start a conversation with me. I read and respond to ALL comments.

If you’re new to Wit & Wisdom, we’d love for you to join our community of 25K readers. The newsletter comes out every two weeks via email. It’s pretty much the only thing in the world that is really free. Please join us.