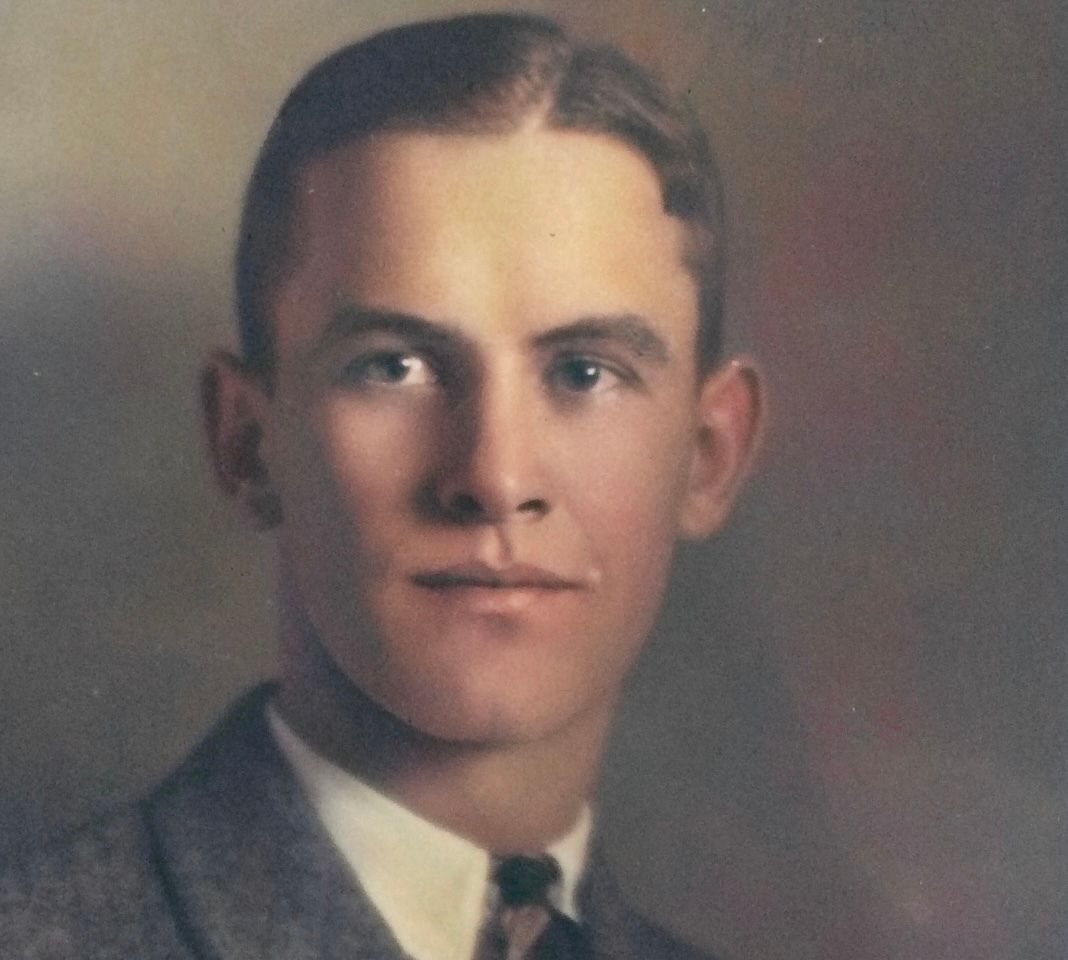

My grandfather died quietly in his bedroom. Not in a sterile hospital room smelling of antiseptic cleaner and wilting flowers. Not in an uncomfortable hospital bed lined with cheap linens. He died at home surrounded by his family.

He died in the same room where he’d slept beside my grandmother for 38 years. In the same bed where his daughters sought refuge during summer storms and bad dreams decades earlier.

AI conversion of my grandfather’s photo by @grok

Everyone knew it was coming. The hospice nurse had left hours before. It was just family. No tubes. No machines. Just the raspy sound of his breathing growing more shallow by the hour. And then, silence.

See, my grandfather knew how to die. Or perhaps more accurately, his (greatest) generation knew something about dying. Something we seem to have forgotten: the art of dying well.

So, when did we get off track? When did we decide that dying is best done alone or with total strangers, far away from the comfort and security of home?

That’s the question raised in L.S. Dugdale’s book The Lost Art of Dying. According to Dugdale, we’ve lost the art of dying well. We’ve transformed death from a spiritual journey into a medical crisis—from a community sharing the burden of grief to an isolated clinical experience.

We’ve taken the most universal human experience and outsourced it to total strangers. We’ve washed our hands of it. It’s too messy and emotional.

“The Medicalization of Death”

Today, we largely outsource our dying to third parties. What was once a community of care, support, and shared grief is now something that requires professional management.

Ever wonder how those amazing hospice professionals seem to know exactly when the patient will die? They’re so good that you can literally calendar a death event. “I’d say you can still take that trip to Albuquerque. But be back by Thursday, no later than 4 p.m.”

See, the body has a script. Hospice nurses know the order like the scenes of a familiar play, as if they’ve seen the same show hundreds or even thousands of times before. Because they have.

Ars Moriendi—The Art of Dying

The medieval Europeans, for all their flaws and limitations, understood something we’ve forgotten. They created an entire body of literature known as Ars Moriendi (“The Art of Dying”).

The Ars Moriendi were practical and spiritual guides for facing mortality with dignity and meaning. People spent years preparing for their final passage.

The medieval Europeans knew that dying was not meant to be a solo sport. In our hyper-individualistic society, we’ve managed to isolate even this most universal experience. We’ve moved death from homes and communities to institutions where the dying person often faces their end surrounded by well-meaning professionals.

Yes, in an era of outsourcing nearly everything, we’ve now outsourced the most intimate human experience to total strangers.

Throughout most of human history, communities knew how to accompany the dying. Death was familiar—not in a morbid sense, but in the literal sense of happening within families. To experience another’s last breath was the most intimate of life’s experiences. It still is.

Today, many people will go their entire lives without witnessing a death until they face their own. How can we possibly know how to die well when we’ve never seen it done?

The Wisdom of Preparation

The medieval Ars moriendi tradition was an invitation to consider your own mortality. See, our ancestors knew that preparation for death isn’t morbid—it’s essential.

Our ancestors didn’t wait until the final weeks of life to think about mortality. They wove it into the fabric of daily existence. Memento mori (“remember that you will die”) wasn’t a dark obsession but a clarifying principle that helped them prioritize what mattered.

AI conversion of my grandparents still photo in 1940 via @grok

Today, we push thoughts of death away until they can no longer be denied. Dugdale suggests a radical alternative: What if we prepared? What if we decided to prioritize dignity over duration. What if, like the medievals, we saw preparing for death not as giving up on life, but as enriching it with perspective and purpose?

Reclaiming Death

What if sometimes the most healing thing medicine can do is to step back and allow natural processes to unfold with appropriate support and comfort?

Reclaiming the art of dying isn’t just about having better deaths. It’s about having richer lives. When we push death into the shadows—we rob ourselves of death’s clarifying power. We miss the motivation mortality provides to live with intention, to prioritize relationships over acquisition, and to value meaning over status.

Our ancestors understood that contemplating the end enhances the journey. That’s why the Psalmist wrote, “Teach us to number our days, that we may gain a heart of wisdom.” Modern science has given us longer lives. But has it given us better ones? Has our medical progress been matched with existential wisdom?

The Way Forward

Dying, like living, is a human experience—not just a medical event. And like all human experiences, it requires not just expertise, but wisdom, love, and community.

My grandfather didn’t die well because he had less medical care—he died well because he had more human care. He was surrounded by stories, history, and love. His death wasn’t a procedure, it was a passage.

Vernon E. Noah (1905-1977)

In chasing longer lives, maybe that’s the art we need to recover: not just surviving longer, but being deeply known, properly grieved, and lovingly accompanied to the end. The forgotten dance of life.

Because, in the end, what we need around death isn’t more medical care.

It’s more humanity.

Okay, this is a really tough subject. I’m betting you have an opinion. I want to hear it. 99% of thoughtful messages will hear back from me. (1% margin for error cause, you know, I’m human.)

If you’re new to Wit & Wisdom, we’d love for you to join our community of 25K readers. The newsletter comes out every two weeks via email. It’s always free, and we are always looking for new friends. Please join us.